When the dreadfully unique South African play Tshepang was first staged back in 2003, I deliberately avoided it.

When the dreadfully unique South African play Tshepang was first staged back in 2003, I deliberately avoided it.

I didn’t have the nerve to see a play about the most horrendous of crimes – baby rape. Why would you want to see such raw trauma acted out in front of you?

But this bold drama by Lara Foot hasn’t gone away, because neither has the issue. At least 20,000 baby rapes are reported every year, plus those of toddlers, children and women. We’re living in a social cesspit, yet Foot has waded in and managed to create a play that is compelling and compassionate as well as brutally honest. It’s a work that wakes you with a start at 4am as your brain rehashes it.

Foot researched and wrote Tshepang: The Third Testament after the rape of baby Tshepang shocked the country and the world. It’s naturally a tough watch, but it’s an important and truly excellent work. It needs that excellence to survive, because otherwise it would be easy to ignore and forget about the play – just like we try to do with the issue itself.

So there we are, watching the clearly traumatised Ruth (Nonceba Constance Didi) scrubbing away frantically at a pile of salt, pain etched in her silent face. A moment later we’re laughing, which isn't what I expected at all. The second character is Simon, played superbly by Mncedisi Shabangu, who paints a vivid picture of this little town where “nothing much ever happens, nothing at all…”

So there we are, watching the clearly traumatised Ruth (Nonceba Constance Didi) scrubbing away frantically at a pile of salt, pain etched in her silent face. A moment later we’re laughing, which isn't what I expected at all. The second character is Simon, played superbly by Mncedisi Shabangu, who paints a vivid picture of this little town where “nothing much ever happens, nothing at all…”

He shows us the bizarre sculptures he makes of nativity scene characters, although he rarely sells them, because no one ever comes. He yells to a neighbour, heckles some guys heading to the shebeen in a mix of English, Zulu and Swati.

This is not a world I’m familiar with, but Shabangu creates it so well I can almost see the dusty streets and ramshackle buildings, and feel the heat of the sun that makes you so thirsty you have to drink. He’s a funny, elegant and beautiful storyteller, and so well directed by Foot that every word and the occasional pause are powerful and poignant.

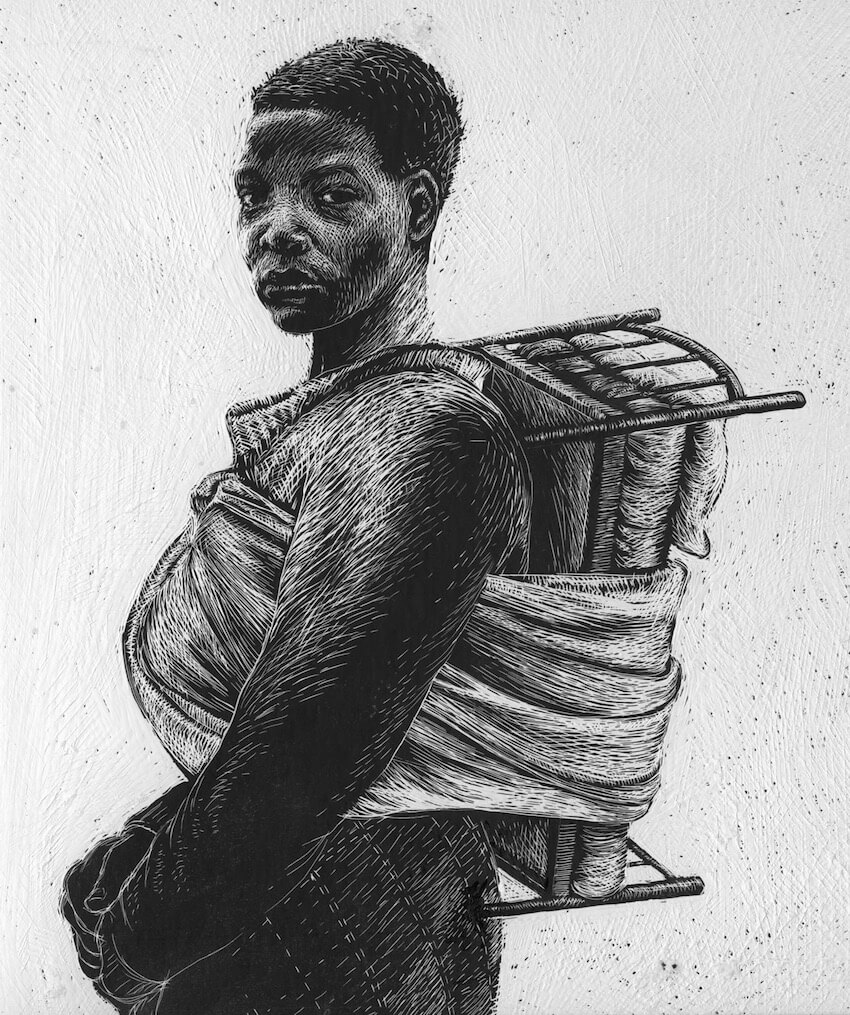

The scenery and props by Gerhard Marx are evocative too, like the tiny bed that Ruth wears strapped to her back where her baby no longer nestles. Or the broom that represents a young boy who was beaten near to death himself, who grows up to be the abuser.

The scenery and props by Gerhard Marx are evocative too, like the tiny bed that Ruth wears strapped to her back where her baby no longer nestles. Or the broom that represents a young boy who was beaten near to death himself, who grows up to be the abuser.

The stage set is simple so it can be performed anywhere – in schools, rural community halls and even in jails. This is the most important part of its work, taking the issue to people who live in circumstances that most readily foment this type of crime. Is that judgemental, saying that wealthier theatre-going people aren’t the target market? Perhaps, but Foot’s research has more accurately defined the scenario where infant rapes occur most often - poor communities with high unemployment, and nothing to do but drink. As Simon puts it, a day that starts with a rough wipe down with a damp cloth, some food, some booze, some sex, some sleep. Repeated day after monotonous day. And sex is a cheap commodity, with the hausfrau that you dump if she demands too much, or the local prostitute who charges a pittance. Or taken forcefully, with someone too young or weak to protest.

Tshepang has won several awards and been translated into Zulu, Afrikaans and Croatian, and has played throughout South Africa and in several cities and festivals overseas. Foot sees it as a story of love and forgiveness, saying that in her search to understand the incomprehensible brutality of this heinous act, she wanted to bring insight to the audience and perhaps offer some sort of healing.

On opening night a couple of people left before the end, but afterwards there was a tangible need to seek each other out and talk. To discuss the issue and our reactions to it, and what future there is for this country where violence, hatred and an utter lack of compassion are so ingrained.

Between them Foot and Shabangu help us to understand the conditions that have led to such widespread horrors. Foot through her measured, poetic and sympathetic script that is dramatic but never melodramatic. Shabangu by building on that with his empathy for the characters, his understated actions or boiling rage, and his magical ability to let the emotions rise and fall. He’s living the story, not just relating it, and his sorrow is palpable. Behind him is always Ruth, the mother of baby Tshepang, a picture of misery as she frenetically scrapes away, angry with herself, lost in her distress.

When they take their bows, both Shabangu and Didi look as if they’re about to cry. As are we all.

Tshepang runs at Joburg Theatre until October 28. Tickets from Webtickets.

Photos: Andrew Brown.