If your holidays are as much about the journey as the destination, dramatic, mind-boggling Namibia is a must.

If your holidays are as much about the journey as the destination, dramatic, mind-boggling Namibia is a must.

It’s a desolate beauty of stark desert, glittering sand dunes, deep canyons and sheer escarpments, and its silent, utterly straight roads disappearing into the horizon emphasis that you’ve entered a different kind of land. Yet this stunning country is utterly indifferent to the fate of travellers who come to admire it.

I mull that over as I sit in the midst of all this emptiness, stranded by a tour bus smelling of burning oil. Rattled into submission by Namibia’s 25,700km of gravel roads and 40°C of sunshine.

I’d last toured Namibia 15 years earlier in a rented 4x4, and got into scrapes like sinking in the sand at Sossusvlei and coasting 44km into Windhoek on an empty tank because we hadn’t seen a petrol station for days. Never again - this is a country that treats city-slicker idiocy with disdain. So I booked an organised adventure, joking that if we broke down this time, I’d sit back with a glass of wine while the professionals fixed it.

I’d last toured Namibia 15 years earlier in a rented 4x4, and got into scrapes like sinking in the sand at Sossusvlei and coasting 44km into Windhoek on an empty tank because we hadn’t seen a petrol station for days. Never again - this is a country that treats city-slicker idiocy with disdain. So I booked an organised adventure, joking that if we broke down this time, I’d sit back with a glass of wine while the professionals fixed it.

The little town of Solitaire celebrates this harsh reality by decorating its streets with dead cars, their rusted skeletons half buried by shifting sands. Vehicles that gave up the ghost when they reached this dorp and conked out, defeated by heat, dust and barren desert.

Namibia is equally tough on its wildlife. At the Cape Cross seal colony I saw many dead pups amid the lolling, barking masses. In Etosha, a statuesque oryx drank from an evaporating waterhole, while skittish zebra tried to decide which they feared most – thirst, or a lion dozing near the water. The threat of instant death proved strongest, and they reluctantly drifted away, still thirsty.

Namibia is equally tough on its wildlife. At the Cape Cross seal colony I saw many dead pups amid the lolling, barking masses. In Etosha, a statuesque oryx drank from an evaporating waterhole, while skittish zebra tried to decide which they feared most – thirst, or a lion dozing near the water. The threat of instant death proved strongest, and they reluctantly drifted away, still thirsty.

The air is breathless the morning I climb Dune 45 at Sossusvlei, a magnificent sand mountain that changes from red to orange to golden with the sun. I start with gusto, and then slow to a slip-and-slide trudge until I reach a plateau. The views are amazing. Raw, dramatic nature entirely surrounding insignificant me. Skittering down the dune’s pristine slope is exuberant fun, and the ever-shifting sand eradicates my footsteps even before I reach the bottom.

The dry pans, or vleis, at Sossusvlei are stunning too, and haven’t changed in millennium. There’s still that photogenic dead tree with twisted branches posing in a stark outline against red sand and bleached white clay. The pans were formed when a river’s attempts to reach the Atlantic Ocean was thwarted by the dunes, and it dried up to leave petrified trees encased in mud.

The dunes march all the way to the ocean, carrying a desert heat that burns away the morning mist along the cold and treacherous Skeleton Coast where shipwrecks abound. The coastal town of Swakopmund is a lovely snoozy little place, with a strong Germanic character from the old colonial days, and I enjoy chocolate torte and a stein of cider in a beach bar.

A highlight here is kayaking near Pelican Point, a strip of land filled with salt farms tinged pink by zillions of tiny shrimps. They’re a delicacy for flamingoes, and we watch thousands of pink birds elegantly mincing through the water.

A highlight here is kayaking near Pelican Point, a strip of land filled with salt farms tinged pink by zillions of tiny shrimps. They’re a delicacy for flamingoes, and we watch thousands of pink birds elegantly mincing through the water.

Then we kayak towards blubbery seals lolling on the beach. The new-born pups are too young to swim – it’s not an inherent talent even for a seal, apparently – so the beach-bound babies cast us envious glances. In six months they’ll be cavorting among the kayaks and chewing on the paddles.

My journey has left a patchwork of memories linked by hours of mesmerising scenery, punctuated by restless nights in hotels where the air conditioning barely stirs the solid heat.

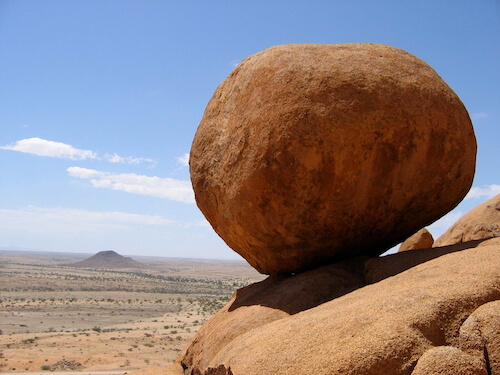

One day after a long, dusty drive it was bliss to jump into the rock pool at Twyfelfontein Country Lodge. The hotel is cunningly hidden behind massive rock formations, and admiring the stars on the way back to its scattered bedrooms is incredible - so many, and so thick in the darkness.

Twyfelfontein is a World Heritage site for its bushmen engravings carved into sandstone with quartz flints. An agile guide led us up boulder-strewn paths to see several clusters of ancient art that has never eroded because it never rains.

Twyfelfontein is a World Heritage site for its bushmen engravings carved into sandstone with quartz flints. An agile guide led us up boulder-strewn paths to see several clusters of ancient art that has never eroded because it never rains.

Close by is a petrified forest of massive trees fossilised into stone over 250 million years, as the huge trunks inched down from central Africa trapped in glaciers. As sweat inches down my t-shirt, I yearn to hug a glacier.

Back on the road, the land changes colour and greenery appears as we approach Etosha Game Reserve. But the green doesn’t encroach on the stark white shimmer of the famous Etosha pan. Even hardy oryx avoid this 130km long wasteland, formed when tectonic plate rumblings changed the course of the Kunene River and the lake it fed dried up. Namibia is a living geology lesson, with everything you ever read in books laid out in front of you.

We don’t find many animals in Etosha since they’ve migrated to soggier zones, but they’ll return winter when it’s slightly cooler and rain has replenished the scenery. Our ranger tells us that 30 rhino were poached here in the past two years, and sadly says the chance of spotting one is extremely rare.

We don’t find many animals in Etosha since they’ve migrated to soggier zones, but they’ll return winter when it’s slightly cooler and rain has replenished the scenery. Our ranger tells us that 30 rhino were poached here in the past two years, and sadly says the chance of spotting one is extremely rare.

Then, like a comedian with perfect timing, a black rhino ambles out of the bushes. He casts us a myopic squint and lumbers across the road in front of us.

Namibia may intimidate me, but I adore its tough-man swagger.