Taking a bath recently, I was surprised when I put my head under water. The room was quiet, but below the surface the peace was destroyed by a loud and constant thrup thrup thrup as the water amplified the sound of machinery somewhere in the building.

Taking a bath recently, I was surprised when I put my head under water. The room was quiet, but below the surface the peace was destroyed by a loud and constant thrup thrup thrup as the water amplified the sound of machinery somewhere in the building.

That must be what it’s like for sea creatures when man invades the oceans with ships, oil rigs and ports. Like an annoying neigbour revving his car outside your home day and night, and you have no way to stop him.

Underwater noise pollution is such a nuisance that whales and sharks are changing their territories, although it’s still an under-investigated field. A far more visible and violent effect of man’s intrusion are the regular collisions of ships with whales – like the MSC cruise ship that docked in New York in May with a 13m sei whale dead across its bow.

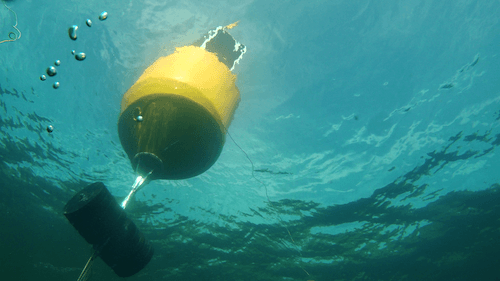

A small IT company in Chile is working to eliminate such accidents by developing hardware and software to monitor and understand underwater sounds. Acústica Marina’s core products are sensors that float underneath buoys and transmit the sounds they detect into the cloud in real time.

The company developed the sensors and the telecoms kit to transmit the signals in-house, and trained AI algorithms to analyse and identify the sounds. The throbbing of a ship can be detected for an astonishing 100km, while the sound of a crab scuttling across the sand may only be detected from 10m. Their sensors also monitor the temperature and salinity of the water.

The company developed the sensors and the telecoms kit to transmit the signals in-house, and trained AI algorithms to analyse and identify the sounds. The throbbing of a ship can be detected for an astonishing 100km, while the sound of a crab scuttling across the sand may only be detected from 10m. Their sensors also monitor the temperature and salinity of the water.

“One of our principal objectives is to develop technology that permits us to listen to the ocean and send alerts in real time to prevent crashes between whales and boats,” says Marcela Ruíz, a marine biologist who co-founded the company with acoustic engineer Roberto Flores.

“We have trained the software to analyse and recognise the data, like the sound of a whale or the sound of a boat. Something interesting is that the human ear can’t hear part of the sound spectrum, but these advanced algorithms have the capacity to analyse it,” Marcela says.

The sensors can be lowered to a maximum of 150m at the moment, but the team wants to make them robust enough to withstand the cold and pressure of greater depths, and still be able to transmit signals in real time. They also aim to develop networks of mobile sensors that could be dropped into ocean rather than attached to buoys, and which could be moved and guided remotely.

“Recently we met some scientists who are studying the ocean where the depth is 8000m, so we have to reinvent the equipment and develop scientific and technological solutions to investigate these places,” Marcela says. “It’s a huge challenge because the pressure could make the equipment implode. Another challenge is Antarctica, where we have to develop equipment that won’t freeze.”

“Recently we met some scientists who are studying the ocean where the depth is 8000m, so we have to reinvent the equipment and develop scientific and technological solutions to investigate these places,” Marcela says. “It’s a huge challenge because the pressure could make the equipment implode. Another challenge is Antarctica, where we have to develop equipment that won’t freeze.”

The technology has several uses, and more are emerging as it hones its offerings. Although they started with a specific aim in mind, the IT path isn’t linear, explains Marcela. “We’re discovering that the technologies can serve more than once objective. We’re discovering opportunities for commercial uses and for solving scientific problems.”

Acústica Marina’s team of 30 includes specialists in maths, statistics, telecoms, IT, acoustic engineering, electronics and AI. Right now they’re installing 10 sensors in a bay from where the mining company Compañía Minera del Pacífico exports its raw materials. The system will send real-time alerts to the cargo ships to request a change of course if a whale is detected. Flores believes a hydro-acoustic monitoring network this big will be a world first.

Another project is in Puerto Williams, one of the most southern cities in the world, which has a high whale presence. There they will help a tourism company conduct whale watching trips with more respect for the whales, by accurately pinpointing their location to get close, but not too close.

The technology could also detect illegal fishing, send warnings of seismic movements, and conduct environmental impact studies before infrastructure is built. The data it collects about whale movements could help biologists understand why migration routes are changing – perhaps because they’re trying to avoid the constant distrubance of manmade objects. “How much noise is this port or this oil rig making, and what is the limit that whales can tolerate?” Marcela asks. “Once we know that, we can campaign for industries to diminish the noise to a level that is tolerable.”

The technology could also detect illegal fishing, send warnings of seismic movements, and conduct environmental impact studies before infrastructure is built. The data it collects about whale movements could help biologists understand why migration routes are changing – perhaps because they’re trying to avoid the constant distrubance of manmade objects. “How much noise is this port or this oil rig making, and what is the limit that whales can tolerate?” Marcela asks. “Once we know that, we can campaign for industries to diminish the noise to a level that is tolerable.”

Her medium-term plan is to monitor the entire Pacific Ocean in real time through a vast network of interconnected sensors gathering data as well as sending shipping alerts.

Eavesdropping on the ocean is only part of the equation, however. The other skill lies in interpreting and understanding what they hear. “The important thing to realise is that 80% of the oceans in all the world are unknown, and we can use technology to understand them,” she explains. Medicines and foods of the future could be in the sea, but the answers are still hidden.

First published in Brainstorm Magazine.