When Hamilton Ratshefola first joined IBM as a young eager graduate, he learned all about technology and salesmanship.

When Hamilton Ratshefola first joined IBM as a young eager graduate, he learned all about technology and salesmanship.

He also learned crucial lessons that still guide his life today – ethics and integrity, and to eschew all forms of racism. Those principles saw him reject blatant expectations of bribery when he formed his own company, Cornastone. They also brought him back to IBM decades later, to repay it for the vital start it gave him and to further its commitment to opportunities-for-all as its Country General Manager.

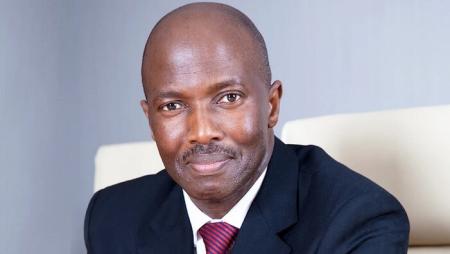

Ratshefola speaks in an engaging, open manner with a twinkle in his eye that gives extra character to his suave, well-groomed demeanour, and listening to him describe IBM as a pioneer against state-sanctioned racism is fascinating.

“In 1990 when there was no BEE and no rules that blacks must be hired, IBM hired me and a bunch of my friends. They had no obligation to hire us, and they continued in the following years to hire black graduates when very few other companies were doing that. IBM’s policy of 112 years has been equal opportunities in all environments. They hired women when women weren’t being hired in the US so they have been torch bearers ahead of the game.”

In those days the MD of IBM SA was Jack Clarke, and he didn’t want a client’s business if it couldn’t accept his black employees. When Ratshefola joined there were already 400 black systems engineers out of 2,000 employees, and many had been housed by the company too. “IBM was the first company to build black people flats in Soweto when the government wouldn’t provide accommodation in the ‘80s. The government didn’t think black people deserved it, so IBM built flats for its employees. IBM taught me ethics and integrity and the higher moral ground.”

It actually taught him too well, he says, by earmarking him as management material and sending him for training in the Europe and the US. Despite that exposure he was kept in the same role and quickly grew frustrated. “They gave me too many ideas,” he says. “When you train people too well they get immensely excited and if you don’t deploy them immediately they go.”

Starting From Scratch

As a hot-headed youngster he also wanted to prove he could succeed on his own merits, not just because he was selling products from a trusted company. He formed Cornastone in partnership with Lufuno Nevhutalu, building everything from scratch and learning budgeting, forecasting, bidding, business models, marketing, strategy and building a team. “You’re now accountable for everything and there’s a lot of work, but you do that and become a better businessman,” he says.

As a hot-headed youngster he also wanted to prove he could succeed on his own merits, not just because he was selling products from a trusted company. He formed Cornastone in partnership with Lufuno Nevhutalu, building everything from scratch and learning budgeting, forecasting, bidding, business models, marketing, strategy and building a team. “You’re now accountable for everything and there’s a lot of work, but you do that and become a better businessman,” he says.

IBM was initially angry about his defection, and even more annoyed when he started selling HP products against them. Gradually those grudges dissipated, and Cornastone became an IBM business partner.

Then other problems arose. After a decade of success, corruption came knocking. “We started getting a lot of unnecessary requests by government to do things which we thought weren’t appropriate, and more and more with every deal,” he says. “I wasn’t winning deals I should be winning and that’s not an environment I wanted to work in. Without that ethical grounding I’d have capitulated and absolutely been tempted during that era of corruption and got involved. But IBM’s background and heritage led me to sell out rather than participate in market practices that are not ethical.”

Ratshefola bowed out and took a year’s sabbatical to consider his next move. As a respected and well-liked black IT leader, job offers were inevitable. He re-joined IBM as a sales executive with the promotion to Country General Manager two years later.

Where’s the challenge in returning to what you know, I ask, and how could working for one of the world’s oldest IT companies possibly excite him? He enthusiastically reels off examples of how IBM totally reinvented its business through new blockchain platforms, artificial intelligence and other technologies for the fourth industrial revolution. “Everything that was at IBM when I arrived in 2013 has been ripped apart and reinvented,” he says. Although acquisitions helped with that, most of its transformative offerings were created internally, with the company filing 9,000 to 10,000 patents every year.

Increased Diversity

His own contribution has seen IBM SA enhance its black profile, with lower-level employees now very representative of the country’s demographics. In fact this year he’s actively employing white students again. “We’re going back to the IBM policy of equal opportunities for all. You have to be representative of the country you work in, so my job was to increase diversity in all divisions without losing competency. This year for the first time we’re giving young white students the opportunity again. We’ve done the work and brought in a lot of black talent and we can’t perpetually keep hiring black over white. We now need to give white talent an opportunity at entry level for them to have an opportunity in this country.”

He also mentors potential young black leaders, teaching them that a leader can be competent, excellent and passionate and still be nurturing, helpful and considerate. He’s excited by IBM’s decision to give Africans free access to an online 4IR self-learning platform, with competencies including blockchain, AI and cybersecurity from elementary to advanced levels. Last year Ratshefola introduced it to 30,000 people at a Bible school, and more than 2,000 youngsters instantly logged on. Some are now getting 4IR jobs with their newly acquired skills. “It’s a $70-million contribution to make sure African children don’t miss out on 4IR opportunities. It’s a real pleasure to be able to run a company like IBM and be able to contribute to society in many ways,” he says.

Reflecting on the 13 years he spent building Cornastone highlights several lessons that made him a better businessman. He realised that being socially-caring manager made him reluctant to make hard but necessary decisions. “It’s fundamental for sustainability to look for quality people to run the business and deliver results and not tolerate complacency and poor execution,” he says.

As a committed Christian, he and his psychologist wife are heavily involved in community programmes for drug rehabilitation. Their five children have grown up and left them as empty nesters with time on their hands, he says. “In their absence I’m putting my life into social responsibility stuff because we have a lot in this country that we need to repair, and there’s a lot we can do.”

First published in Brainstorm Magazine, June 2020.