Another Women’s Day has come and gone, and if statistics held true, seven more women were murdered.

Another Women’s Day has come and gone, and if statistics held true, seven more women were murdered.

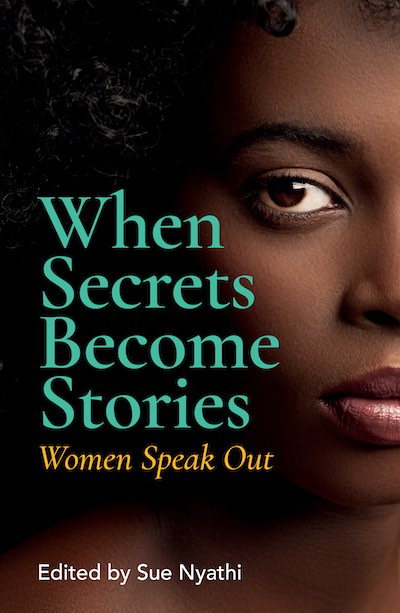

I spent Women’s Day reading When Secrets Become Stories, a compilation of short, brutal and true stories edited by Sue Nyathi. Domestic violence feeds on shame and silence, Nyathi says, so she encourages women to bravely share what was once secret, to cast off the shame and reclaim their power. “Only exposed wounds can heal, the hidden ones fester and cause you to rot inside,” she writes.

Gender-based violence affects women in all countries and all walks of life, but it’s particularly acute in South Africa. That’s not dramatic hyperbole. Google “which countries have the worst rates for sexual abuse?” and the answer is instant. The top hit says: “South Africa has the highest rate of rape in the world of 132.4 incidents per 100,000 people.”

It’s a shameful top-four slam for Africa in these stats from the World Population Review, with Botswana having 92.90 cases per 100,000, Lesotho 82.70 and Eswatini 77.50. In comparison, the United States has a rape rate of 27.3. The real figures are far higher due to under-reported for fear of victim shaming, reprisals, and the knowledge that perpetrators are rarely punished. In a survey by the South African Medical Research Council, approximately one in four men said they had raped.

South Africa is also in the global top five for femicide with seven murders daily, half killed by someone they knew, and a quarter by their intimate partner.

When Secrets Become Stories is a disturbing catalogue of the many ways women live in fear or discomfort, and the ways men simply don’t see women as their equal to be respected and treated decently. Its pages reek with the male sense of entitlement.

In her opening chapter, Nyathi says she has repeatedly been told something that sounds unthinkable - that a real woman has the strength to bear abuse because there’s a correlation between the amount of suffering they endure and the love they receive. Escaping abuse is a privilege only a few women enjoy, she adds, and we constantly have to be hypervigilant. If you still think that’s an exaggeration, read the stories.

Some are well-crafted, while others have less polish and rely on raw emotion for their impact. There’s one memory about being a four-year-old and wishing she was dead to escape her abuser. One by a prosecutor trying to decide if a raped child can give evidence in court, although the mere fact that she’s here is “proof that major injustices have already been committed.”

Another writer was a victim of tennis coach and child rapist Bob Hewitt. She had to change her name to avoid the stigma and is now an activist against child abuse in sport. Others were raped repeatedly by their fathers.

Abuse and harassment aren’t confined to the home. Farah Fortune reminds us that they’re rife in the workplace too, with threats to sink your career if you don’t keep quiet.

Some writers have gone on to form happy relationships, while others still have trust issues. Ayanda Xaba writes: “The men I have been exposed to over the past 15 years mostly believed that a woman is there to serve their physical needs and have made me fear being in a relationship.”

Robyn Porteous writes that once you’re courageous enough to tell someone, they say maybe it wasn’t that bad, maybe you are over-reacting. Maybe you didn’t fight hard enough. But that very sentence is appalling – why should women have to fight for the right not to be attacked? It’s been years since Porteous was abused, yet she still struggles to sleep, works too hard and runs marathons to prove that her body is more than an “aging crime scene.”

Many memoires show how the female is always believed to be in the wrong, or not believed at all. Even the words we use to describe sexual behaviour lay bare how ingrained our warped attitudes really are. Promiscuous men are dubbed Casanovas - so much more glamorous than the female version of slut or whore.

South Africa’s outrageous degree of gender-based violence largely stems from the way boys are raised. In many homes they’re not raised at all, just neglected to grow up without any moral guidance. Boys must be taught that you don’t raise your hand to a woman or demand your conjugal rights, says Bongi Mdluli. She also makes the crucial point that mothers must change how they treat their daughters too. Many girls are still raised to believe that marriage and having children are the end game to aspire to, or even their only choice in life. As the stories repeatedly show, those young girls are often so flattered by the attention of a man that they’ll take whatever scraps of affection a boyfriend deigns to give without questioning whether this is what they really want. If girls were raised to have self-confidence and independence, the cycle could be disrupted.

Sadly, some women help to perpetuate misogyny: black mothers who tell their daughters that men are superior and reign supreme; Muslim mums raising their girls to be subservient; white mothers who don’t believe a daughter who tells them she was assaulted by a family friend.

Melody Zonda, a former Mrs Universe South Africa who was physically abused, urges the readers to learn to love themselves unconditionally and not seek that love from others. “I realised that putting the responsibility to be loved on someone else meant that I was opening myself up to abuse and that it took my power away,” she says.

Perhaps these 26 stories by abused women could alert young girls to the male behaviour to be wary of, and kindle questions about their future choices. But that depends on them reading it, and this isn’t the sort of book they’re likely to pick up unless they’re already in a troubled mind space. Perhaps it should be introduced in schools. I’d love to hear the debates it would spark in the classroom.

When Secrets Become Stories is edited by Sue Nyathi and published by Jonathan Ball at R272.