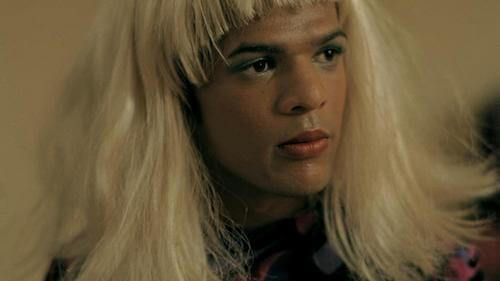

At the end of the movie A Lucky Man, the camera hones in on a gnarled face with a scar running its full length and a mouthful of metal where teeth ought to be.

At the end of the movie A Lucky Man, the camera hones in on a gnarled face with a scar running its full length and a mouthful of metal where teeth ought to be.

It’s the ravaged face of Ernie ‘Lastig’ Solomon, a reformed gangster who somehow made it to 54 while many of those around him died. I didn’t ask how many died because of him, since that would be an impertinent question to a notorious Cape Flats gangster.

Solomon was having the final word in a movie about his life, filmed in 2013 in the community where he took up social work to persuade youngsters not to follow his lead. In the film, he described how lives and communities are ruined by the gangs. How the graveyards are full of brothers killed by brothers, fathers killed by sons, because they’re allied to different clans.

Now Lastig himself is dead, shot on November 20, 2020 in a hit in Boksburg near Johannesburg. He’d made it to 62, but narrowly, since this was the second attempt to assassinate him this year. Presumably his good intentions to quit the gangs and become a social worker didn’t go too well, then.

Now Lastig himself is dead, shot on November 20, 2020 in a hit in Boksburg near Johannesburg. He’d made it to 62, but narrowly, since this was the second attempt to assassinate him this year. Presumably his good intentions to quit the gangs and become a social worker didn’t go too well, then.

A Lucky Man was written and directed by Gordon Clarke and filmed using Cape Flats locals, largely with no acting experience. For all that it promised a strong storyline around an intriguing life, its slow pace made it far from a thriller. It was disjointed at times, and while using local characters added authenticity, it impaired the quality of the acting. It felt more like a public service movie that should be touring schools and community centres. Except the life it portrayed probably still looked more glamorous than any other choice the Cape Flats offers.

Producer Mark Fyfe denied that A Lucky Man might make gangsterism seem an attractive career option. “There’s a very real message we are portraying that gangsterism isn’t the way to go. The warning at the end is very stern. It’s not a gangster movie. It’s a longing for belonging and a search for identity and we hope we are showing they’ve got it all wrong.”

Producer Mark Fyfe denied that A Lucky Man might make gangsterism seem an attractive career option. “There’s a very real message we are portraying that gangsterism isn’t the way to go. The warning at the end is very stern. It’s not a gangster movie. It’s a longing for belonging and a search for identity and we hope we are showing they’ve got it all wrong.”

Fyfe was motivated both by the aim of producing a good movie and by the chance of doing some good. Yet the filming was quite traumatic. “I was absolutely flabbergasted to see the extent of the decay in these communities. Every day was a surprise with police raids and being exposed to what really happens and seeing the rotten underbelly. It’s so horribly ravaged by drugs and alcohol, and it literally is on our doorstep.”

About 72% of Cape Flats kids go to jail, and 90% of those re-offend, he said. About 60% of the country’s gang and drug related crimes occur in the Cape Flats, and 63 shootings happened on school premises in the previous year. Going to jail is almost seen as a rite of passage. “There’s a perception that going to jail enables you to equip yourself with the necessary life skills to survive, and that’s a fallacy. If the message gets home to one 16-year-old that he doesn’t have to do gangs then my job is done. That sounds very cheesy, but that’s what we all feel.”

Yet when I asked what the alternative life is, he didn’t have one. “There is no solution - that’s the bottom line,” Fyfe said. “We just witnessed a horrific upswing of violence in the Cape Flats but it isn’t even reported any more. People are absolutely numb to their plight. They have been cast aside by the previous regime and cast aside even more by the current regime. There is no political will to fix the problem, the perception is it’s unfixable, it’s gone too far.”

Yet when I asked what the alternative life is, he didn’t have one. “There is no solution - that’s the bottom line,” Fyfe said. “We just witnessed a horrific upswing of violence in the Cape Flats but it isn’t even reported any more. People are absolutely numb to their plight. They have been cast aside by the previous regime and cast aside even more by the current regime. There is no political will to fix the problem, the perception is it’s unfixable, it’s gone too far.”

When I talked to Solomon he initially spoke in broken English, but as he got going his passion lubricated his sentences. The movie shows what can happen to kids who grow up in a bad area or whose families don’t want them, he said. Solomon got his nickname ‘lastig’ (nuisance) because to his uninterested father and extended family, that was all he was. “The children become gangsters because nobody likes them. They are not in a family, so they look for a family in the streets and join the gangs.”

He’d started working with Western Cape Community Outreach to persuade the gangs to end their violence. It was tough and often fruitless work, made harder since the gangs killed one of the outreach leaders. “But that’s not stopping us from making peace in the community,” he said. “Some of them listen but those who are not listening we try again and again - we don’t stop talking to them.”

Solomon, who was also runing a fish shop, said his goal was to help youngsters choose a better life. One of his own sons had been killed a decade earlier. “We are fighting our own people and killing our own people and it’s not right. The children don’t ask for this gangsterism,’ he said. “The way I grew up friends of mine died and I feel sad about it, sometimes I cry. People who kill other people never think of the people who are going to cry over us.”

Solomon, who was also runing a fish shop, said his goal was to help youngsters choose a better life. One of his own sons had been killed a decade earlier. “We are fighting our own people and killing our own people and it’s not right. The children don’t ask for this gangsterism,’ he said. “The way I grew up friends of mine died and I feel sad about it, sometimes I cry. People who kill other people never think of the people who are going to cry over us.”

He also didn’t have much of an alternative to offer, however. “The work opportunity isn’t there for our people and the opportunity for education isn’t there. The schools look like prisons. How can our children get better when the schools look like prisons?” he said. “We want the government to help us.”

To make sure A Lucky Man reached its target audience, it was edited into 18 punchy clips of four minutes each for viewing on a cellphone using Mxit, a popular networking forum in the Cape Flats at the time. Fyfe said the team also took it to the townships to spread its core message: “Stay out of jail, stay away from drugs. It’s a disaster, it will kill you.”

For Lastig, it finally has.