I felt a bit of a wimp when I booked a tour through Peru and requested a train ticket to Machu Picchu.

I felt a bit of a wimp when I booked a tour through Peru and requested a train ticket to Machu Picchu.

I’d weighed up the options for reaching the stunning lost city of the Incas high in the mountains, and figured I shouldn’t be ashamed to let the train take the strain. Far better than a four-day hike at high altitude where you struggle to breathe, let alone walk, sleep in a tent, and try to ignore 499 other people plodding along around you while you pretend you’re an Inca warrior entering the city in the original, noble way.

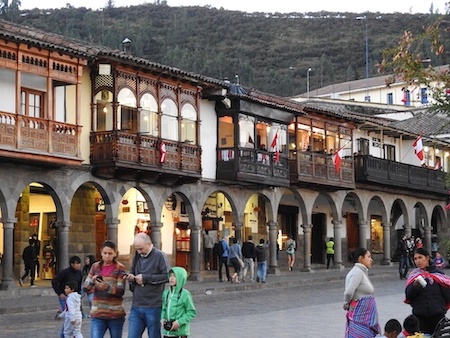

Besides, not torturing myself on a mountain gave me extra time in Cusco, a gorgeous old city that trekkers whizz through in a day. Now I had time to take the free walking tour, the open top bus ride, admire other Inca treasures, have a massage and eat in nice restaurants instead of cooking over a camp fire.

Cusco was the capital of the Inca Empire that flourished from 1400 AD until Spanish conquers arrived 1532, bringing war and diseases that rapidly wiped them out. The city was studded with fine buildings and palaces, large plazas and a fortress. Its highlight was Qorikancha, a temple complex where some rooms were literally covered in beaten gold. It clearly shows the fine masonry skills the Incas are famous for, with massive stone blocks that fit together perfectly without mortar. Since this is earthquake territory they were designed to withstand quakes too, with walls that gradually slope inwards and stones that jiggle on top of each other in situ.

Cusco was the capital of the Inca Empire that flourished from 1400 AD until Spanish conquers arrived 1532, bringing war and diseases that rapidly wiped them out. The city was studded with fine buildings and palaces, large plazas and a fortress. Its highlight was Qorikancha, a temple complex where some rooms were literally covered in beaten gold. It clearly shows the fine masonry skills the Incas are famous for, with massive stone blocks that fit together perfectly without mortar. Since this is earthquake territory they were designed to withstand quakes too, with walls that gradually slope inwards and stones that jiggle on top of each other in situ.

Cusco is a great base for visiting other Inca sites too, including Pisac with rows of agricultural terraces and clusters of crumbling houses. Ollantaytambo was still being built when the Spanish arrived, and you can see giant blocks of granite hewn from a quarry that were abandoned as they fled.

An open top bus takes me to a weaving centre using wool from cute alpacas roaming outside, some with natty dreadlocks trailing to the ground. I buy a gorgeously soft sweater, bearing in mind my tour guide’s warning that anything claiming to be “100% alpaca is 100% a lie.” In the gardens, an Inca shaman burns coca leaves and wafts the smoke over us, then asks my name and chants a blessing. Being blessed by a descendent of the powerful Incas somehow makes me feel invincible.

An open top bus takes me to a weaving centre using wool from cute alpacas roaming outside, some with natty dreadlocks trailing to the ground. I buy a gorgeously soft sweater, bearing in mind my tour guide’s warning that anything claiming to be “100% alpaca is 100% a lie.” In the gardens, an Inca shaman burns coca leaves and wafts the smoke over us, then asks my name and chants a blessing. Being blessed by a descendent of the powerful Incas somehow makes me feel invincible.

One thing I avoid is a ‘cleansing’ session with ayahuasca, a hallucinogenic plant extract. A Shaman Shop in one of Cusco’s many ancient courtyards offers the ritual if you’ve fasted for 24 hours. Even then the plant will purge everything in your body before hallucinations begin.

A leaflet poetically describes it as ‘a liquid laxative for the soul’ to cure illnesses, communicate with the spirit world and reveal the mythological origins of life. “You will go on incredible journeys through mountains, deserts and jungles,” it tells me, but I decide to see the scenery in an unhallucinogenic state, and put the leaflet back.

Another alley leads to a cultural centre with crafts shops, grazing llamas and an Inca descendent playing traditional music on a conch shell, pan pipes made from condor feathers and a flute carved from llama bone.

Another alley leads to a cultural centre with crafts shops, grazing llamas and an Inca descendent playing traditional music on a conch shell, pan pipes made from condor feathers and a flute carved from llama bone.

Finally I take the train to Aguacalientes, a town that has grown up specifically to serve the Machu Picchu trade. The train is clean, spacious and punctual, and uniformed attendants serve complementary drinks and biscuits as a commentary tells us about the places we’re rattling through. Then we clunk backwards and jerk forwards again. This is the ingenious zig zag method, the commentary proudly announces, getting us down a mountain by shunting back and forth on tracks running parallel to each other.

Aguacalientes is in a stupid place, a waiter in the town confides as he serves me two happy hour cocktails of pisco sour. It’s in an earthquake-prone valley with no escape route and one day it will all be gone, he gloomily predicts. When I was there it was buzzing with a massive craft market, hotels and restaurants lining its steep streets, and a hot springs bathing centre where hikers can clean up and relax their weary bones.

The next morning at 4.30am I join a queue waiting for buses that start at 5.30am, delivering a constant stream of tourists to Machu Picchu itself. The road is a series of switchbacks and is crumbling under the strain, while the ruins themselves feel damagingly overcrowded.

Machu Picchu was a royal estate for emperors and nobles, but was abandoned only 100 years after its construction as the Spanish began their brutal conquest of South America. What makes it so special is that it was never discovered by the Spanish, and remained intact instead of being trashed. It’s less intact now than it was when American archaeologist Hiram Bingham was led to it by local farmers in 1911. Yet its scale and beauty and the stunning location on a mountain surrounded by misty peaks rising through the jungle create an extraordinary experience.

Machu Picchu was a royal estate for emperors and nobles, but was abandoned only 100 years after its construction as the Spanish began their brutal conquest of South America. What makes it so special is that it was never discovered by the Spanish, and remained intact instead of being trashed. It’s less intact now than it was when American archaeologist Hiram Bingham was led to it by local farmers in 1911. Yet its scale and beauty and the stunning location on a mountain surrounded by misty peaks rising through the jungle create an extraordinary experience.

I have to ask whether the Incas were exceptionally tall, since the stone steps between the buildings are a stretch even for my long legs. No, they were short, our guide says, but very strong and muscular. I sit on one of the wide agricultural terraces held up by hundreds of thousands of carefully placed stones, and contemplate the amazing craftsmanship surrounding me. This feels right - not racing to tick off views from every angle, but quietly admiring the Temple of the Three Windows and the Temple of the Condor, with each stone fitting as snugly as a jigsaw piece.

When I meet my trekking colleagues later, their stories confirm that taking the train was a smart move. Everyone has blisters and aching bodies, and some are limping. One poor woman’s body let her down when the altitude hit 4000m, and the guides loaded her onto a pack mule since she could no longer walk. Her friend spoke of mountain paths so narrow that she took one shuffling step at a time, in constant fear of falling.

Yes, hiking had been worth it, they said, but with a hesitancy that sounded like they were trying to convince themselves as much as me.